From Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) Health News

(This article is from a partnership that includes WBUR, NPR, and KFF Health News.)

BOSTON

A 17-year-old boy with shaggy blond hair stepped onto the scale at Tri-River Family Health Center in Uxbridge, Massachusetts.

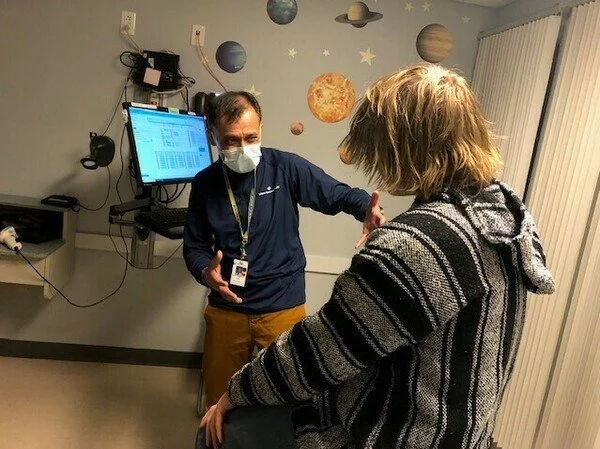

After he was weighed, he headed for an exam room decorated with decals of planets and cartoon characters. A nurse checked his blood pressure. A pediatrician asked about school, home life and his friendships.

This seemed like a routine teen checkup, the kind that happens in thousands of pediatric practices across the U.S. every day — until the doctor popped his next question.

“Any cravings for opioids at all?” asked pediatrician Safdar Medina. The patient shook his head.

“None, not at all?” Medina asked again, to confirm.

“None,” said the boy, named Sam, in a quiet but confident voice.

Only Sam’s first name is being used for this article because if his full name were publicized he could face discrimination in housing and job searches based on his prior drug use.

Medina was treating Sam for an addiction to opioids. He prescribed a medication called buprenorphine, which curbs cravings for the more dangerous and addictive opioid pills. Sam’s urine tests showed no signs of the Percocet or OxyContin pills he had been buying on Snapchat, the pills that fueled Sam’s addiction.

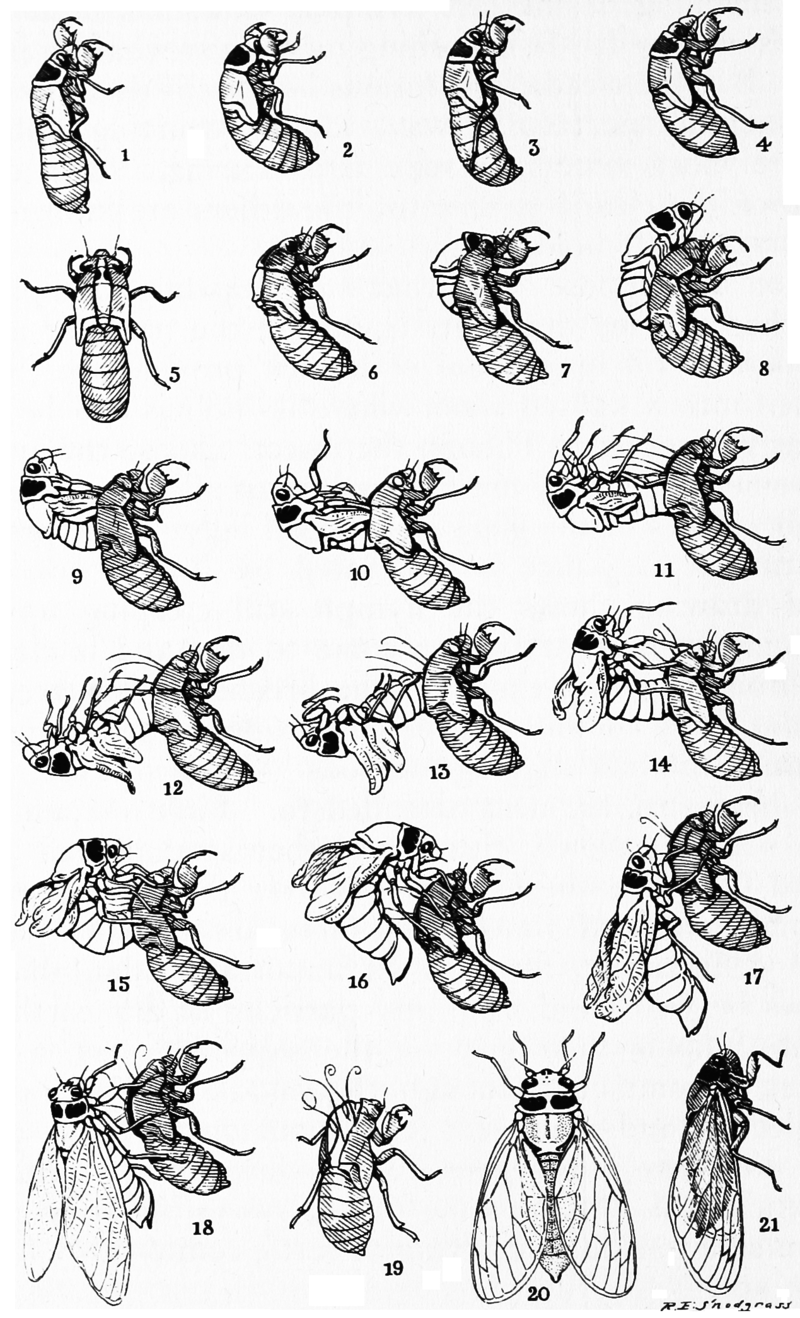

As part of his pediatric practice, Safdar Medina treats opioid use disorder. During a recent appointment at a clinic in Uxbridge, Massachusetts, Medina switched a teenage patient’s buprenorphine prescription to an injectable form and checked in about his school and social life.

“What makes me really proud of you, Sam, is how committed you are to getting better,” said Medina, whose practice is part of UMass Memorial Health.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends offering buprenorphine to teens addicted to opioids. But only 6% of pediatricians report ever doing do, according to survey results.

In fact, buprenorphine prescriptions for adolescents were declining as overdose deaths for 10- to 19-year-olds more than doubled. These overdoses, combined with accidental opioid poisonings among young children, have become the third-leading cause of death for U.S. children.

“We’re really far from where we need to be and we’re far on a couple of different fronts,” said Scott Hadland, the chief of adolescent medicine at Mass General for Children and a co-author of the study that surveyed pediatricians about addiction treatment.

That survey showed that many pediatricians don’t think they have the right training or personnel for this type of care — although Medina and other pediatricians who do manage patients with addiction say they haven’t had to hire any additional staff.

Some pediatricians responded to the survey by saying they don’t have enough patients to justify learning about this type of care, or don’t think it’s a pediatrician’s job.

“A lot of that has to do with training,” said Deepa Camenga, associate director for pediatric programs for the Yale Program in Addiction Medicine, in New Haven, Conn. “It’s seen as something that’s a very specialized area of medicine and, therefore, people are not exposed to it during routine medical training.”

Camenga and Hadland said medical schools and pediatric residency programs are working to add information to their curricula about substance use disorders, including how to discuss drug and alcohol use with children and teens.

But the curricula aren’t changing fast enough to help the number of young people struggling with an addiction, not to mention those who die after taking just one pill.

In a twisted, deadly development, drug use among adolescents has declined — but drug-associated deaths are up.

The main culprits are fake Xanax, Adderall or Percocet pills laced with the powerful opioid fentanyl. Nearly 25% of recent overdose deaths among 10- to 19-year-olds were traced to counterfeit pills.

“Fentanyl and counterfeit pills is really complicating our efforts to stop these overdoses,” said Andrew Terranella, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s expert on adolescent addiction medicine and overdose prevention. “Many times these kids are overdosing without any awareness of what they’re taking.”

Terranella said pediatricians can help by stepping up screening for — and having conversations about — all types of drug use.

He also suggests that pediatricians prescribe more naloxone, the nasal spray that can reverse an overdose. It’s available over the counter, but Terranella, who practices in Tucson, Arizona, believes a prescription may carry more weight with patients.

Back in the exam room, Sam was about to get his first shot of Sublocade, an injection form of buprenorphine that lasts 30 days. Sam is switching to the shots because he didn’t like the taste of Suboxone, oral strips of buprenorphine that he was supposed to dissolve under his tongue. He was spitting them out before he got a full dose.

Many doctors also prefer to prescribe the shots because patients don’t have to remember to take them every day. But the injection is painful. Sam was surprised when he learned that it would be injected into his belly over the course of 20-30 seconds.

“Is it almost done?” Sam asked, while a nurse coaches him to breathe deeply. When it was over, staffers joked out loud that even adults usually swear when they get the shot. Sam said he didn’t know that was allowed. He’s mostly worried about any residual soreness that might interfere with his evening plans.

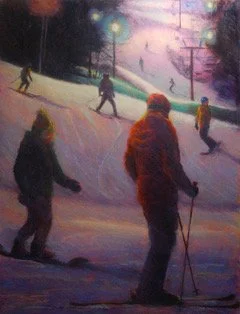

“Do you think I can snowboard tonight?” Sam asked the doctor.

“I totally think you can snowboard tonight,” Medina answered reassuringly.

Sam was going with a new buddy. Making new friends and cutting ties with his former social circle of teens who use drugs has been one of the hardest things, Sam said, since he entered rehab 15 months ago.

“Surrounding yourself with the right people is definitely a big thing you want to focus on,” Sam said. “That would be my biggest piece of advice.”

For Sam, finding addiction treatment in a medical office jammed with puzzles, toys and picture books has not been as odd as he thought it would be.

He mother, Julie, had accompanied him to this appointment. She said she’s grateful that the family found a doctor who understands teens and substance use.

Before he started visiting the Tri-River Family Health Center, Sam had seven months of residential and outpatient treatment — without ever being offered buprenorphine to help control cravings and prevent relapse. Only 1 in 4 residential programs for youth offer it. When Sam’s cravings for opioids returned, a counselor suggested Julie call Medina.

“Oh my gosh, I would have been having Sam here, like, two or three years ago,” Julie said. “Would it have changed the path? I don’t know, but it would have been a more appropriate level of care for him.”

Some parents and pediatricians worry about starting a teenager on buprenorphine, which can produce side effects including long-term dependence. Pediatricians who prescribe the medication weigh the possible side effects against the threat of a fentanyl overdose.

“In this era, where young people are dying at truly unprecedented rates of opioid overdose, it’s really critical that we save lives,” said Hadland. “And we know that buprenorphine is a medication that saves lives.”

Addiction care can take a lot of time for a pediatrician. Sam and Medina text several times a week. Medina stresses that any exchange that Sam asks to be kept confidential is not shared.

Medina said treating substance-use disorder is one of the most rewarding things he does.

“If we can take care of it,” he said, “We have produced an adult that will no longer have a lifetime of these challenges to worry about.”

Martha Bebinger is a WBUR reporter.

marthab@wbur.org, @mbebinger